The Stranger in the Shelter

Told here in full for the first time, this is the horrifying story of the first murder on the Appalachian Trail, the kidnapping that followed, and how one woman learned to survive.

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

Three people met in the Georgia woods. They were two young men and a girl not yet 18. They were a drifter and a pair who barely knew each other. They were, all three, green to the outdoors, new to the dragon-backed highlands near the southern end of the Appalachian Trail. One died in those mountains. A second forfeited any shot at a normal life. Just one of the three has outlived the story. Until now, 44 years after the fact, that survivor has shared it with few. Three people met in the Georgia woods, and this is what happened.

It begins with the girl.

A typical girl of the mid-seventies American South, in most respects. In love with her dog, her friends, and summer days wasted in adventure yarns and mysteries. In Jethro Tull records and card games and movie dates. In canoeing the pond out back of her family’s house in Sumter, South Carolina.

Sharper than average: Margaret McFaddin Harritt could dive so deep into books that the world around her disappeared, and she could apply the same focus to any task at hand. She finished high school in three years and turned 17 just days before arriving at the University of South Carolina.

She looked even younger than she was. But she was also a headstrong kid. Daring. Hungry for the new and exotic. South Carolina wasn’t much for counterculture in the fall of 1973, but she found a pocket of it a few blocks from USC in Columbia’s Five Points district. Hippie boutiques. Hole-in-the-wall restaurants. The Joyful Alternative, which sold incense, New Age books, and roach clips. A new outdoor shop called the Backpacker.

Margaret found a job in Five Points, waiting tables at a popular restaurant, Capri’s Italian. Which is what she was doing one night in March 1974 when in walked tall, long-haired Joel Polson.

He was slender, fit, and wore shorts year-round. His mustache and goatee signaled that he was older than Margaret—by nine years, she’d come to find out. But otherwise he seemed an unspoiled child of nature, a guileless friend to all.

And from that first night, Joel talked nonstop about a great adventure he had in the works. He planned to hike the Appalachian Trail, all 2,200 miles of it. It would take months. And hey, he told her, you should come with me.

Margaret laughed off the idea. She’d just met him. Besides, she was no athlete—she hadn’t intentionally exercised a day in her life—and slogging up mountains didn’t sound like fun. But Joel kept coming back, still talking up the trip. She ran into him at the Joyful Alternative, where he talked about it more. Before long, two thoughts began to crystallize.

One, she liked this Joel. Not in a romantic way; he was more buddy material than boyfriend. But she found that he was deeply interested in the world around him. He was relentlessly upbeat. Not least, he was generous: he wanted to pursue big, life-shaping experiences that he was eager to share.

And two, she would not be returning to USC in the fall. She felt out of place there, uninspired by her classes. She wasn’t sure what she would do.

Perhaps a long walk was just the way to work that out.

Margaret owed much to her DNA. She was fun-loving like her physician father, a hard-playing freethinker who friends called Wild Bill. And she was willful like her mother, whose childhood polio had not kept her from college and a career as a clinical pathologist, raising four children, and juggling a crowded social calendar.

Like both of her parents, she was intellectually curious. She devoured books on Eastern religions. And in their pages she detected threads that resonated with her—that time is vast and human life short. Death would come for her, as it did everyone. Fearing it didn’t make much sense. Fear in general didn’t.

The sum of all this: Margaret said yes. “I can remember sitting in her front yard and her telling me about the trip,” says Mary Jac Brennan, Margaret’s closest friend since first grade. “I’m sure I knew about the trail, but I’d never known anyone who did that kind of stuff.”

In 1974, few did. The previous year, just 93 people completed a through-hike of the entire trail, and the feat did not yet inspire the public’s imagination. Margaret knew almost nothing about the AT. Still, in early May, she found herself 38 miles from its southern terminus at Springer Mountain, Georgia, beginning their first full day of hiking.

They’d started their journey the evening before, at a road crossing at Tesnatee Gap, but got such a late start that they were able to cover only a couple of miles, in darkness. Now Margaret got a first good look at her surroundings. In spring, the southern Appalachian forests are flooded with light (maples, oaks, and tulip trees are just beginning to bud) and wildflowers—buttercups and purple trilliums, toothworts and mayapples, the neat white radials of great chickweed. In every direction mountains form blue-gray ramparts against the sky.

It was stunning. But the view carried a price: the trail climbed steadily, unmercifully, and burdened by their overloaded external-frame packs, the unseasoned hikers felt every foot. It wasn’t long before Margaret had a blister forming on her heel. They paused to tape moleskin over it. About a mile on, they broke for lunch. They encountered a party of foresters armed with chainsaws, on the hunt for blowdowns, and stopped to chat. They rested once more a little farther on, and again after that.

Late in the afternoon, they were relieved to reach a long descent. At the bottom, a sign pointed the way down a 190-yard side trail to the Low Gap shelter. They’d covered just six miles but agreed: the day ended here.

Then as now, the shelter was a lean-to perched high on concrete pilings in a glade hemmed by a curving brook. There, under the hut’s gabled roof, they found another hiker already settled on the bare plank floor.

They must have made quite the first impression. Margaret had her hair in pigtails, looked barely into her teens, and was dwarfed by her enormous red JanSport pack. Joel wore a pith helmet, the headgear favored by olden-day jungle explorers, equal parts swashbuckling and absurd.

By comparison, the stranger was nondescript. He was a little older than Joel, by the looks of him, and much smaller—five inches shorter and slight of build. He had a wispy mustache and horn-rimmed glasses. What remained of his receding blond hair was combed straight back and fell over his collar.

As she shook off her pack, Margaret asked his name. Ralph, he replied.

Were there clues that something awful was about to happen?

No. None that Margaret detected, anyway. Ralph appeared harmless, though certainly down on his luck, with the dark, desiccated skin of a heavy smoker who’d gone awhile without a shower. In the shelter beside him was a meager pile of gear: blanket, leather jacket, canvas rucksack.

After a few minutes of conversation, Margaret crossed the clearing to wash up in the stream. Joel sidled up close. He didn’t know that he trusted this Ralph character, he told her, keeping his voice low. Surprising talk, coming from him.

Ralph didn’t look like a hiker, Joel explained—he was wearing suede crepe-soled desert boots, and didn’t have any proper gear. He glanced back over his shoulder toward the shelter. They’d left their packs right next to the guy, he whispered. For all they knew, he could be stealing their stuff right now.

They hurried back to the shelter. Ralph hadn’t moved. Their gear was untouched. He watched as, a little chastened, they strung up a clothesline and hung their socks and T-shirts. They started a fire and cooked dinner, offering him some. He demurred.

As they ate, Ralph left the shelter and wandered into the trees, returning with an armful of wood for the fire. He made another trip for more. Went back a third time.

Well, maybe he’s all right, Joel commented to Margaret while Ralph was gone. He’s probably OK. Still, he told her, they should leave first thing in the morning. He’d wake her, and they’d get hiking straight away. They’d have breakfast when they were a mile or two up the trail to the north.

Margaret crawled into her sleeping bag not long after. Darkness had yet to fall. As she drifted off, the men built the fire into a fierce blaze. Neither said much.

She woke to Joel urging her to get moving. Margaret sat up in her bag. Morning had come, and he was already loaded up; his big green pack leaned against a tree outside, cinched tight. She watched as he walked to the stream, splashed water on his face, and doubled back toward the fire ring. At the same time, Ralph threw off his blanket and stepped out of the shelter.

She was lacing a boot when there came a loud, sharp noise, a blast, and when she looked up, Joel had dropped into an awkward crouch. His head rested on the fire ring. He was motionless.

Before Margaret had time to process the scene, Ralph was leaping into the shelter to stand over her. In his hand was an enormous revolver.

Wait, what? “Roll over,” Ralph said. “Be quiet.” He tied her hands behind her back with twine. What had just happened? He ordered her to her feet, then guided her up the narrow path that led to the privy and into the trackless woods beyond. “Is Joel dead?” she dared to ask.

“No,” Ralph told her, “he’s just hurt.” He said it quickly.

“Could you pull him away from the fire ring so he doesn’t get burned?”

Yes, Ralph said, he’d do that. He stopped her beside a slim hardwood, ordered her to sit on the ground, pulled her legs around the tree, and tied her feet together. He blindfolded her. “Do I have to gag you?” he asked.

“No,” Margaret replied. “What are you going to do with me?”

“I don’t know,” he said.

He walked off. Margaret sat on the forest floor, surrounded by the sounds of trees and birds, frantic. This couldn’t be real. She willed herself to calm down, to imagine that it was all a story, a fiction. She hoped Joel wasn’t badly hurt. Ten minutes passed, maybe fifteen.

Footsteps. Ralph removed her blindfold, untied her, and led her back to the shelter. Joel was nowhere to be seen. She asked Ralph where he was.

“I got rid of him,” he said.

Joel Eugene Polson: April 26, 1948 to May 9, 1974. Remembered today, when he is remembered at all, for his unfortunate place in history—the first documented murder on the Appalachian Trail.

In the decades since, seven other hikers have died in acts of violence on the footpath. Most of those crimes have attracted national attention, if for no other reason than the AT’s status as one of the safest places around.

A few southern newspapers wrote of his murder in the days after. But the story soon faded, and today Joel Polson’s life and death are usually dispensed with in a sentence or two. Who he was, and how he passed the 26 years before that May morning, are such a blank that many mentions of him in print and online misspell his name Polsom.

This much is known: He was from Hartsville, South Carolina, a paper-mill town 60 miles northeast of Columbia. The youngest of three children born to John E. and Bonnie Tedder Polson, a mill worker turned jeweler and a farm-raised homemaker.

Joel was intrepid as a kid, into scouting, playing soldier. Then, when he was 13 or 14, he suffered a mysterious accident. “Joel climbed up a tree onto the roof of the garage, and he apparently fell down,” says his brother, Johnny. Their parents, who’d been out for the day, returned to find Joel dirty and discombobulated. “We never got a clear story of what happened, because Joel didn’t remember,” Johnny says. “He was thrown off by some sort of mental thing from that fall.”

Whatever his condition, by the time he was able to return to school, he was two years older than his classmates. Even so, he seemed “childlike, kind of naive,” a friend, Kenneth Krueger Jr., remembers. “Not of the world. He didn’t see people as threatening.”

He was also shy and nerdish, clumsy in his interactions. Photos from his high school yearbooks depict a bespectacled straight arrow with a mission-control haircut and a fondness for cardigans and chinos. “He didn’t have that many friends,” his brother says. “And of course, talking to girls, he didn’t have any skills there.”

Still, Joel was difficult to overlook at Hartsville High. He got into photography, and he and his camera became fixtures at every campus event. Classmates nicknamed him Flash.

That primed him for further involvement. By his senior year, he’d been active not only on the newspaper and yearbook staffs, but in student government, a slew of clubs, and the junior and senior class plays. He was president of the Photography Club, was a DJ on the school radio station, and worked the counter in the student store.

Flipping through the yearbook, you’d think that awkward Joel Polson was among the most popular kids in school.

At the shelter, Margaret was numb with shock. Joel was probably dead. It made no sense. The men had not said a word to each other that morning.

Ralph ordered her to eat and drink while he went through Joel’s pack. He asked whether Joel had any money. Traveler’s checks, she managed. Where? She pointed out where Joel stashed them. She had change in her pocket. She handed it over.

Pack up, Ralph told her. He led her back into the woods—deeper this time, 200 yards from the shelter. She asked whether he was going to kill her. “You really don’t have any reason to,” she told him. “I didn’t do anything to you.”

“Well,” Ralph said, “neither did Joel.”

He had her again sit facing a tree and once more positioned her legs around the trunk, binding her feet together. He tied her hands behind her back. He covered her backpack with leaves and wedged his own rucksack behind her as a backrest. I’ll leave you here, he told her. I’ll leave a note in the shelter saying where you are.

Ralph had brought Joel’s pith helmet along, and now he turned it upside down, filled it with water, and placed it beside her. He dropped a bag of granola in her lap. He had her demonstrate that she could reach both with her mouth. It could be that somebody will come in an hour, he said. Then again, it might be tomorrow.

This time he dispensed with the blindfold. Instead, he balanced Joel’s watch on a log so that she could read its face, then stalked off through the trees.

Margaret watched the sweep of the second hand. It seemed preternaturally slow. Minutes crawled by. She strained her ears, dreading the sound of footsteps, certain that if Ralph returned it would be to kill her.

After fifteen minutes, here he came. Being dead didn’t frighten her. Getting that way, she realized, did. She found herself thinking, with eerie calm: OK God. Here I come.

She was lacing a boot when there came a loud, sharp noise, a blast, and when she looked up, Joel had dropped into an awkward crouch. His head rested on the fire ring. He was motionless.

Ralph surprised her. I can’t leave you here, he announced. What if it’s days before anyone shows up? You’d die, and I don’t want that.

I didn’t want to kill Joel, he said. I just wanted his gear. I had to do it because he was such a big guy. But, he said, he had never “whacked a chick before.”

So you have a choice, Ralph told her. You can stay here if you want. Or you can hike out of the mountains with me. When we get to the next highway, I’ll let you go home.

Margaret did not dwell on her options. She did not want to sit tied up in the woods. She wanted to get away from the shelter and out of Georgia, and yes, she’d be walking with Joel’s killer, but that was secondary to getting out of there.

“Untie me,” she told him.

A few minutes later, they were packed up and headed back to the AT, Margaret in the lead, Ralph and his gun a pace behind. At the junction, they could have turned south, backtracking to a road less than five miles away. Instead, Ralph ordered her north.

Listen up, he said as they walked. I’m going to let you go. But if we run into anyone before we reach civilization, and you say anything—or do anything to signal that there’s something wrong—you’ll all die. And I’ll kill you first.

After high school, Joel continued to hone his skill behind a lens. He landed pictures in the local papers and won first place at the 1970 Darlington Arts Festival. “If he had lived, he would have been an outstanding photographer,” his friend and distant cousin Myra Polson says. “I mean, he would have been going to National Geographic.”

Joel hiked frequently into a local arboretum to photograph flowers and the blackwater swamp at its heart. Perhaps the beauty he found there kindled his interest in the natural world, because during a stint at Hartsville’s Coker College, he immersed himself in “trying to save the planet,” Krueger says.

He took up cycling, too, and invested in a lightweight road bike he took on marathon rides across the coastal plain. Around 1970, he pedaled from Hartsville to Kent, Ohio, and a couple of years later, says his brother, he set out to ride across the country.

Joel’s trip ended in Texas. “He got hemorrhoids,” Johnny Polson says. “He came back on a Greyhound with his bike.”

Inevitably, his interest in the outdoors and arcane gear fused into a new passion: Joel started talking about hiking the Appalachian Trail.

You set the pace, Ralph said. If you need to rest, stop. Anything you need, we’ll do it.

His kindness chilled Margaret. She believed none of it. She was the only person who could link him to a murder. Surely he planned to kill her.

But for now she was still alive, and she recognized that staying that way meant doing everything he said, buying one minute at a time.

For nearly four miles out of Low Gap, the trail followed an old roadbed ruffed with ferns. On their left rose dark stone, bearded in moss and punctuated with small waterfalls. On their right the ground fell sharply away. Margaret expected at any moment that Ralph might shove her over the precipice or shoot her in the back and kick her down the mountainside. She was certain he’d do it. It made sense that he would.

She steadied her nerves by talking. She said it seemed like he was running from something and asked what it was. He’d been in and out of the pen, he replied. The FBI was probably looking for him.

He was preoccupied. He was wearing Joel’s heavy pack, which was sized for a man with a longer torso. The straps carved into his shoulders, and he couldn’t get the hipbelt to ride comfortably. It was he, not Margaret, who needed to stop every few minutes.

They were resting not far into the hike when two men with chainsaws came into view, one of them the same forester she and Joel had spoken with the day before. Margaret panicked. This was no chance for rescue. Just the opposite: if the forester saw that she was hiking with a different man, she was sure Ralph would start shooting.

And in fact, the guy did notice. “Oh yeah,” he said. “We saw y’all yesterday.” She held her breath.

He said no more about it. They couldn’t dawdle, he said. Their ride was picking them up miles to the south later that afternoon.

Ralph asked about the next road crossing to the north.

It’s a long way, the man replied. A good hike.

The men hurried off, unaware of their luck, leaving Margaret with a deepening dread that she and Ralph would spend the night in the woods.

Five years out of Hartsville High, Joel bore scant resemblance to the clean-cut kid in his old yearbook photos. He looked like a hippie out of central casting—beard, granny glasses, hair spilling past his shoulders and held in place with a headband.

But appearances aside, he was out of step with the Woodstock generation. He lived with his parents. He remained a quiet misfit. Though he was good-looking—“beautiful,” Myra Polson says—no one recalls him having a girlfriend. “He was just a friend to everybody,” says a college buddy, Marguerite Ewing. “He was happy to be by himself, and he was really happy to make other people happy.”

He continued to dive deep into hobbies: He took a liking to bluegrass tunes and built his own washtub bass, carrying the unwieldy instrument wherever he went. He bought a fiddle, too. Family and friends never heard him play it, but it ranked high among his possessions.

It’s too bad, Ralph said, that we didn’t meet under different circumstances. If all this hadn’t happened, I could have really liked you.

In time, Joel moved to Columbia and was hired on as a night watchman at the Joyful Alternative. The post included a cot in the back, which is where he was living when he first walked into Capri’s and met Margaret.

By then he’d read everything he could find about the Appalachian Trail and was a regular at the Backpacker, where he made an impression on the owners, brothers Lewis and Malcolm Jones. “Joel Polson was one of the most gentle persons I’ve met through the years,” Lewis says. “A true gentle person, quiet and trustworthy.”

He was also broke—he didn’t earn nearly enough to cover the cost of gear. All he had to offer was that fiddle. “He said that if I would let him get some equipment and sign a note, he would leave the violin with me, and when he got back from his adventure he’d pay us back.”

“He outfitted himself with a tent, sleeping bag, all the equipment he’d need,” Lewis says. “And he went on his way.”

The old roadbad ended, and Margaret now led Ralph over a narrower, more arduous path. It was studded with rocks and knuckled with roots, and it rode the knobby spine of a ridge high above the infant Chattahoochee River. She spurred their conversation as they tackled a series of short but steep ascents. He told her he’d busted out of jail. She learned that he was born “up north” but had been “out west,” up in the mountains. There he could scratch by with just a pocketknife. Not so in these southern Appalachians: here he felt out of his element. He wanted to get back west, which meant moving light and fast—which meant stealing Joel’s gear.

The afternoon sun crossed the sky. The AT traversed several slides of jumbled boulders, and the hikers’ progress, never brisk, slowed as they picked their way across. Just beyond, they came to the Rocky Knob shelter, where they rested before descending a steep, 150-yard side trail to a spring.

After filling his canteen, Ralph pulled a trail map from Joel’s pack and was surprised to find that the next road crossing was less than three miles away. Even they could cover the distance by nightfall.

Joel asked many to join his hike—friends, acquaintances, and, as in Margaret’s case, near strangers. All but Margaret dropped out as the time to leave approached.

He arranged for his mother to mail-drop supplies and, miffed that the only available AT patch bore the legend Maine to Georgia, carefully embroidered his own reading GEORGIA TO MAINE. Margaret had never met a man who could embroider. She was impressed.

They refined their timetable: Joel would attend a fiddling convention in North Carolina and from there make his way to Springer Mountain. In the three weeks before Margaret’s last exam, he’d bang out the trail’s 76-mile Georgia section, then he’d tell her where to meet him and she’d take a bus from Columbia. They’d hike together from there.

One logistical hurdle remained. Knowing that her parents would never let her hike alone with a man, Margaret concocted a lie: she would be one of 15 college students Joel would lead on the trip. She enlisted him as coconspirator and introduced him to her folks in mid-April 1974.

Her father, an avid hunter, was excited by the adventure and evidently satisfied that Joel was fit to lead it. He bought Margaret the gear she’d need and snapped a Polaroid of her wearing her oversize pack. She looked tiny and impossibly young in the image—slight, baby-faced, feigning hardy courage with one foot propped up on a chair.

The night before Joel left, he and Margaret stayed with her elder sister, Polly. Joel spread his sleeping bag on the kitchen floor. Polly’s young daughter had received baby chicks for Easter, and the bright yellow birds “drove him crazy all night,” Polly remembers. “He was a lovely young man, and he made light of the fact that he slept with the baby chicks.” In the morning, he was off.

A week later, he was back. Once again he’d developed hemorrhoids, and he’d made it only to Tesnatee Gap. He killed time while Margaret wrapped up her classes.

On Monday, May 6, the two left Columbia by bus for Atlanta. The next day they took another bus into the mountains and caught a ride to the trailhead at Tesnatee.

Change of plan, Ralph announced. He would not let Margaret go when they reached the road. He needed time to work out his next move, and he wanted her with him. They would hitch to the nearest town and get a motel room, and he’d let her go in the morning.

It was good news and bad. The good: Ralph might not kill her here and now. The bad: Ralph would kill her just the same. And first she might have to actually hole up with him in a motel.

They clambered out of the hollow, up a series of short, steep climbs, and then down the rocky, hourlong descent into Unicoi Gap. They heard passing cars long before they saw Georgia Route 75 through the trees. Ralph repeated his warning: say anything and everyone dies.

A few minutes after they reached the blacktop, a young woman pulled over and offered them a lift. Once in the car, Ralph told her they had traveler’s checks but had lost their IDs. Did she know of a place that would overlook that?

She might, the woman replied. Nine miles south of Unicoi Gap, she stopped the car outside a restaurant in the north Georgia burg of Helen.

The name of the place—Wurst Haus—offered a clue to what set Helen apart. Facing the decline of its logging industry, the town had reimagined itself as a tourist draw: a storybook Bavarian village, its every building revamped with towers, chalet rooflines, and alpine gingerbread.

It was into this discordant setting that Margaret and Ralph now stepped. In the restaurant, with Ralph holding his gun a foot away, Margaret asked whether she could cash a $20 traveler’s check. Of course, she was told. Where in town could they stay? Just up the road, came the reply.

The Chattahoochee Motel was an unassuming place, with six rooms facing the road and its namesake river chattering fast out back. Ralph did the talking this time. He asked for a room, handed over $10, and signed the register Mr. and Mrs. Joel Polson.

Margaret entered their room with a fast-beating heart. She fully expected he would rape her. Just as likely, this is where he’d kill her. But once he’d closed the door behind them, Ralph was interested only in whether the TV carried word that Joel’s body had been found.

Nothing appeared on the local news. At a restaurant next door, they bought food and beer and brought it back to the room. They watched an Elvis Presley movie. Ralph practiced Joel’s signature, so he could cash his traveler’s checks. He told Margaret that if she wanted to keep a memento of Joel, she was welcome to go through his pack. She left it as it was.

She asked to take a shower. It did not give her the brief peace she’d sought: Ralph followed her into the bathroom, ushering a fraught moment. But he didn’t lay a hand on her, didn’t so much as look at her—he was there, it seemed, solely to keep her from climbing through the window.

You know, Ralph told her, I could tell you were scared when we were hiking. You kept turning around, like you thought I was about to shoot you. I almost gave you the gun just to calm you down.

It’s too bad, he said, that we didn’t meet under different circumstances.

If all this hadn’t happened, I could have really liked you.

Margaret drifted off, exhaustion overpowering her fear, as Ralph sat alert in a chair, the gun beside him. Though it might seem impossible, she slept through the night; it was well past sunup when she opened her eyes to find him still sitting there. They packed and walked to the Wurst Haus to cash more traveler’s checks, Margaret amazed by every new step he allowed her to take. The restaurant had no money in the till. At a gas station up the street, Ralph forged Joel’s signature, and they walked out with $20.

They returned to the Wurst Haus for coffee. He was still going to let her go, Ralph said. But he couldn’t think of allowing her to hitchhike home to South Carolina—there was no telling what sort of person might pick her up. So they’d find a bus station, and then they’d go their separate ways. Ralph had a map of Georgia and figured they could get a bus in Cleveland, nine miles to the south. They started through town, thumbs out. A car pulled over.

At Cleveland’s Trailways station, Margaret asked the man at the counter for a ticket to Columbia. Well, he said, from here you’d have to go to Atlanta first. But Cornelia, a town to the southeast, has a Greyhound station. You can catch an eastbound bus there.

They hitched another ride. The Greyhound station occupied a downtown storefront, and when Margaret and Ralph arrived shortly before noon, they found the door locked and a sign on the glass: Gone to the doctor. Be back afternoon.

They walked to a nearby bank to cash more traveler’s checks. After a quick lunch at a restaurant around the corner, they returned to the bus station, where the manager appeared and unlocked the door. Margaret bought a $10 ticket for Columbia. Ralph stepped up to the counter. He was still keeping Margaret at point-blank range, so he couldn’t very well hide where he was going: he paid $3 for a ticket to Atlanta.

His bus, due in first, was running late, so Ralph talked. He’d probably been stupid to let her live, he told her. He knew she’d go to the police and that the cops would be looking for a man with a big green pack. He counted on having a few hours’ head start.

I promise you, he said, that if you call the police as soon as I leave, and they’re waiting when I get to Atlanta, innocent people are going to die. I’ll start shooting, and I won’t care who gets hurt.

You should write a book about this, he said. You could make some money.

Then his bus arrived. His pack was loaded into the cargo hold. He climbed aboard. Margaret watched the bus pull away.

She sat in the waiting room, awed that she was alive, scared that he’d be back, and wanting nothing but to get home to her mother. She sat, immobile, until her own bus arrived a short time later.

It was dark when the Greyhound reached Columbia. From a station phone booth, Margaret called her elder brother, who lived in the city, but got no answer. She called her parents in Sumter. No one picked up.

So she dialed the Columbia police. Someone’s been killed in Georgia, she said, and I need to tell you about it. Could you come get me?

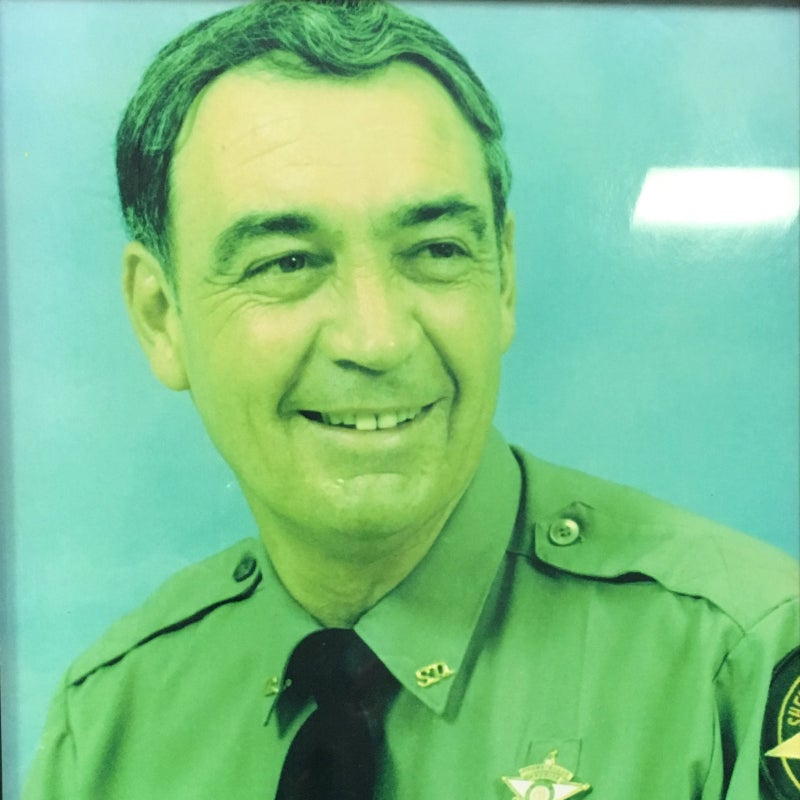

The Low Gap shelter stands just within White County, Georgia. At 11:15 that night, the sheriff’s office got a call from a police captain in South Carolina relating that a teenager in hiking boots and pigtails had just told him what he’d later describe as “a right weird story”—that a homicide had occurred at Low Gap and that a body could be found nearby.

Sheriff Frank Baker summoned backup from the Georgia Bureau of Investigation. In the wee hours of Saturday, May 11, GBI special agent Stanley L. Thompson was roused from his bed and dispatched to White County. Well before dawn, Thompson joined Baker at the crime scene. The sheriff had already found Joel.

He lay covered with leaves and sticks, across the stream from the shelter. His clothes were in disarray, suggesting he’d been dragged by his armpits. “The subject’s head was in a plastic bag and the bag had been tied around his head with a piece of string,” Thompson wrote in his report. “This was done apparently to keep the blood from being strewn around the area.”

An autopsy found that a .38-caliber bullet had entered Joel’s skull just behind his left ear, ripped through his cerebellum, and come to a stop beneath his scalp above and behind his right ear.

That was a break for investigators. They had the bullet.

Margaret described her ordeal in an hours-long interview two days later. She was as confused as her listeners about one piece of the narrative. “It was just strange that he knew the whole time that it would be because of me that he would get caught and all [but] was still letting me go,” she said.

“I don’t know what his motive was or anything, but he was unbelievably kind to me. He really was.”

While she gave her statement, Joel’s family and friends gathered in Hartsville for his funeral. Just after, his distraught mother had to be hospitalized.

A week after the killing, on May 16, the Atlanta Police Department received a telephone tip: a woman said she’d met a man matching the newspaper’s description of the Appalachian Trail murder suspect. She knew where he lived.

Agent Thompson and Sheriff Baker drove to Atlanta, where police obtained a search warrant for the man’s apartment. He wasn’t home, but inside they found Joel’s backpack, his clothes and camping gear, and a revolver containing four live rounds and one empty cartridge. Thompson waited inside for the tenant to return. Late that afternoon he did. “He was just meek as a lamb, from what I remember,” Thompson says. “He had no choice, because I stuck a .357 right in his nose.”

Police identified him as Ralph Howard Fox. He was 31, born and raised in Detroit. Like Joel, he was the youngest of three children in a solidly middle-class household. The similarities ended there.

“He started early on getting into trouble,” his sister, Corrinne, says. In his teens, Ralph kidnapped a girl from a party he threw while his parents were away, she recalls. At 17, he was arrested for car theft, and again a year after that for breaking and entering. In 1963, when he was 20, he ran off to New Mexico with a teenage girl and was arrested for statutory rape and contributing to the delinquency of a minor. Her name was Ann. He married her a few months later.

In March 1964, with his 16-year-old wife expecting their son, Ralph forced a Detroit high school junior into his car at gunpoint, then drove her 13 miles to a wooded lover’s lane in Troy, Michigan. An alert cop came upon them as he was tying the girl’s hands behind her back.

Ann divorced him. The state gave him 15 years, but he served only a fraction of that before he escaped from the Michigan State Prison in Jackson. Details of his breakout are lost—Michigan prison officials say his file was destroyed years ago—but in October 1969, he was recaptured in Miami and returned to Jackson.

“He was never out of prison very long before the next thing happened,” Corrinne says. Indeed, she says, while out on parole he broke into Ann’s apartment and lay in wait for her. When she walked in, he opened fire with a rifle. He missed.

“I wouldn’t say I’ve done anything all that extraordinary, but I have very much taken it to heart that I was spared for something,” Margaret says.

Ralph eventually fled the state. He bounced around New Orleans for a while, then Fort Lauderdale, and later Atlanta. He stepped onto the Appalachian Trail for the first time five days before killing Joel.

Margaret picked him out of a lineup. He admitted owning the gun, which he said he’d bought on a Florida beach; it was later matched to the bullet taken from Joel’s head. He confessed to stealing Joel’s gear. He described tying Margaret up, returning for her, and their hike to Unicoi Gap. “I was just trying all the time to keep her scared, you know,” he told Thompson after his arrest, “so that she wouldn’t run for help or anything like that.”

Ralph did not explicitly confess to murder, however, or explain just what had happened that morning at Low Gap. When Sheriff Baker asked him whether Joel was “a friendly type of fellow,” Ralph replied: “I didn’t talk to him much.”

Thompson: “Did you need the gear, the camping equipment and all that—is that the purpose?”

Ralph: “No.”

Thompson: “Did you get into an argument, some kind of argument, or anything?”

“No,” Ralph told him, “just something—I’ll have to wait for a lawyer.”

He said no more. When he was indicted for murder the following October, Ralph pleaded guilty. He was sentenced to life in Georgia State Prison.

Ralph Fox, a.k.a. Inmate D-21795, spent most of the next 17 years behind bars. But when his older brother died, in July 1991, he was granted a one-month reprieve to attend the Michigan funeral. That furlough morphed into parole, with his supervision transferred to Michigan authorities.

And so Ralph gained a tentative freedom, and he moved in with Corrinne in Lapeer County, Michigan, about 50 miles north of Detroit. He could have made a new start. He could have demonstrated that his behavior at Low Gap had been an aberration and that the mercy he showed to Margaret Harritt, while unsettling in its own right, was truer to his character. That in his middle years he was a wiser and better man.

At first it seemed he might. He came home deeply aged and depleted by prison. He was quiet, agreeable. “I thought he had totally changed,” Corrinne says.

But after seven months of liberty, he failed to appear at a meeting with his parole officer and didn’t turn up at home or his job. About a week later, on March 5, 1992, police were called to a muddy field in rural Lapeer, where they recovered the nude body of 29-year-old Diane Good of Detroit. She’d been strangled.

They also found evidence that a car had recently been mired in the mud. Canvassing local towing companies turned up a driver who recalled pulling a blue-gray Mercury Cougar from the field. Its owner had given his name as Ralph Fox.

Police issued a nationwide alert for man and vehicle. Two days later, Ralph was arrested in Skagit County, Washington, as he tried to break into a parked car. A Lapeer jury convicted him of murder that November. Ralph did not take the stand. His only statement on the matter came at his January 1993 sentencing. “I’d just like for the record to know,” he said, “that I did not have anything to do with the murder of Diane Good.”

Circuit Judge Martin E. Clements wasn’t having it. “Mr. Fox, you were convicted of murder before in another state,” he said. “You are now convicted of two murders in your lifetime. I am satisfied that you pose a substantial risk to a free society, and that you should never be let out of prison.

“Ever,” he added. “For any reason.”

Thus it went. Some years after Ralph was again locked up, he was diagnosed with lung cancer, and in June 2003 he was transferred to the state prison hospital. He died there the following month.

Corrinne has not been able to reconcile the “very soft-spoken” brother she knew with the killer he was. The summer after he died, she and Ralph’s son took his cremated remains to a swinging bridge over eastern Michigan’s Rifle River and dumped them into the water.

By that time, traces of Joel Polson were becoming elusive. His parents were dead. Friends and relatives had scattered, and his simple, flat gravestone in the family plot provided no information beyond the dates of his birth and death. No marker bore his name at Low Gap or anywhere else on the AT. Of the hundreds, perhaps thousands, of photographs he took, few survived outside of the yearbooks he worked on.

His fiddle endured, however. When the Jones brothers back in Columbia heard that Joel had been killed, they were “just devastated,” Lewis says. “We went over to Joel’s funeral, my brother and I.”

“I wanted to give them this violin,” he says, but the Polsons said no—Joel had made a deal with the store, which the family felt it should honor. “They said they would like me to keep it.”

And he did, for more than 40 years. “I had it refurbished,” Lewis says. “And my granddaughter was interested in playing the violin, so I gave it to her.”

She “stuck with it very diligently for a couple of years,” he says, then lost interest. If she did not resume playing, Lewis planned to get it back. “I’ll always have that violin. It’ll be in the family,” Lewis said this spring. “This is a special instrument.”

Lewis didn’t know at the time that his granddaughter had quit playing for good and that her family had stashed the fiddle in the attic. That a leaky pipe had dripped water on it until the seams burst and the wood turned to mush. That it went out with the trash.

Three people met in the Georgia woods. One died there, leaving scant trace of his decent and well-meaning life. A second followed nearly thirty years later, with little but heartache to mark a squandered existence.

But this story ends, as it began, with Margaret. She turned 62 not long ago. She is married, with two children, three stepchildren, and two grandkids, and lives in southern Europe, where her husband was based when they met. Their hilltop home, fringed with palms, olives, and citrus trees, offers a sweeping panorama of rolling grassland studded with Bronze Age megaliths. She passes afternoons tending to an ambitious herb garden.

Her thoughts rarely wander back to May 1974. When they do, she can revisit those days with almost clinical detachment. “I’ll explain to people that it almost feels like it happened to somebody else,” she says. “But that’s not exactly accurate. It’s very much a part of me, but the whole thing is so surreal that it almost feels like it’s a movie.”

More than forty years passed before she decided to share her story—first with the Appalachian Trail Conservancy, in 2015, and now for this article. Time has brought her little clarity about why it happened. Who steals a backpack by walking up to its owner and, without so much as a word, shooting him in the head? Who lets the sole witness get away? Why did Ralph handle her with such fraternal care when he’d brutalized others?

Perhaps even more, she is amazed by her own behavior. She had always assumed that if confronted with violence, she’d “scream and fight and get crazy and run away.”

“But a person does not know how you’re going to react in that critical moment until you’re in it,” she says. “I had this calm. Adrenaline—who knows what it was? But I was calm.”

“I am not a passive person. But I was passive then, and it probably saved my life.”

The arc of that life has been a rebuttal to her two days with Ralph. Later in 1974, she got her own place outside Sumter and found work at an orchard, overseeing its production of tree seeds. The job, solitary and outdoor, appealed so much that in 1975 she enrolled at Clemson University and took up forestry.

She did a lot of thinking. “I decided I’d start being and doing what I was supposed to,” she says. “I was a teenager hanging out, smoking pot, and doing the things you do at that age. Within a year or two of this experience, I had quit all drugs, all alcohol. I was much more serious.”

“It was almost as if God took a big old branch and whacked me across the head and said, ‘Wake up. Don’t wait forty years. Don’t wait five years. Wake up right now.’”

Any other person terrorized in the woods might avoid them. Margaret went on to get her doctorate, which required several years in the tropical forests of Brazil. She joined the U.S. Agency for International Development, managing projects in Honduras, Nicaragua, and Bolivia. She spent much of a decade in jungles. She was twice posted to Pakistan and worked in five former Soviet republics.

Once, years after he’d been locked up, Ralph mailed Margaret’s parents a copy of the Georgia State Prison newspaper he edited, and she worried that he knew their address. Another time, a friend remarked that killers in Georgia could expect to serve just seven years, and she was again anxious that he might be free to hurt her loved ones.

But those episodes aside, her hours with Ralph, certain that she was about to die, seemed to have inoculated her against fear.

Today, post-retirement, she continues to visit the world’s hot zones as a contractor with her old agency. “She doesn’t mind wearing bulletproof vests and being delivered by Marine helicopters,” her sister, Polly, says. “It’s not as though she’s throwing herself in the face of danger, but at the same time it doesn’t scare her.”

Margaret herself is matter-of-fact about her life’s trajectory. “I wouldn’t say I’ve done anything all that extraordinary, but I have very much taken it to heart that I was spared for something,” she says. “Maybe this experience helped me see that life is a fleeting moment, so grab it and go.”

Most days, she is quick to point out, do not require bravery. She wakes up surrounded by beauty. She digs in her garden. She roams the countryside around her home.

Hiking out there is calming, restorative. A reboot. The light looks different in that part of the world. Everything is suffused with gold.

And the grasslands are wide open. You can see for miles.

Nothing is hidden.

Earl Swift (@EarlSwift1) is the author of Chesapeake Requiem: A Year with the Watermen of Vanishing Tangier Island. He wrote about the wreck of a tangier fishing boat in June.